“The split between words and reality takes its revenge, even though the author be of good faith.” - Czesław Miłosz

I started reading The Captive Mind as part of 75 Hard (more on that program in another post). It was a somewhat difficult read for a history flunkie like myself, but because 75 Hard demands that you finish the books you start, I stuck with it. It’s the story of Stalinism in Poland under Russian rule, and particularly the mental gymnastics practiced by those forced to endure it—especially writers and artists.

I’ve always wondered why communism—an idea that, while I don’t subscribe to it, seems motivated by fairness and concern for the working class—leads to murderous regimes when put into practice. I picked up the book to learn more about that (as it’s 1600 fewer pages than Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s famous trilogy). And it helped clear up that mystery, for sure. What I didn’t expect from the book was such incredible insight—and perhaps inadvertent advice—on writing.

That shouldn’t surprise me, given the book’s focus on the psyche of the creative, and the fact that Miłosz himself remained an honest and courageous memoirist under a regime of political suppression of thought and expression. Throughout his dissection of the rise and fall of his classmates and peers, Miłosz emphasizes the inherent value of he whose soul is “loaded with that little-known internal energy which bears the name of poetry.”

Much modern commentary on the craft of writing focuses on finding one’s “voice”—an exercise I find counterproductive, as it implies the search for something elusive rather than the honing of an author’s natural inclinations. Miłosz understands voice as I do: under “the pressure of an all-powerful totalitarian state,” where “a premium is placed on every type of conformist, coward, and hireling,” he writes, it is “among the ‘criminals’ [that] one finds a singularly high percentage of people who are direct, sincere and true to themselves.”

The government of Miłosz' time demanded (under threat of imprisonment) "dialectical materialism" from its poets, novelists and creative writers—a patriotic twaddle that precluded any real exploration of the human condition, lest such reveal the widespread discontent wrought by the new order. But the latter produces better writing, says Miłosz, who watched as gifted fellow authors were systematically drained of their genius. Each soul in turn was sold to the advancement of the political program, his initial reluctance giving way to the need for survival, the balm of self-deception, and finally the distraction of wealth and political power.

I wonder if the casual communist-apologists of my old bohemian friend group, who were unmoved by economic arguments, would think twice of a regime that would raid their emo poetry slams. Conveniently for my former friends, the democracy under which they live protects their criticism of the same. But I digress.

“Subject matter that is close to the longings of mankind emancipates the written word from the shackles of passing literary fads,” Miłosz writes.

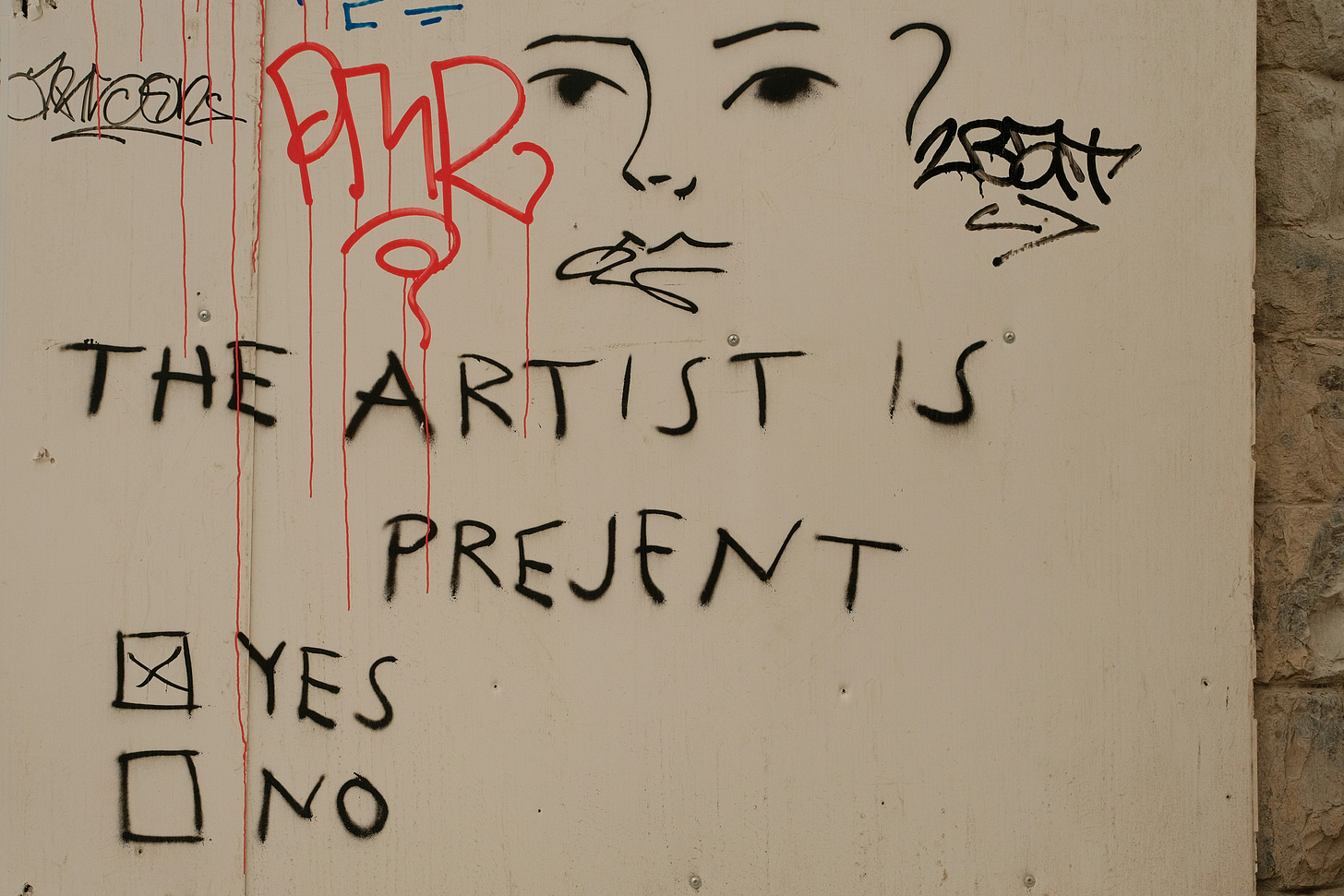

I am reminded of our own passing literary fads, and the damage they’ve wrought upon creativity. While decidedly less genocidal, the “progressive” West’s obsession with its idiosyncratic brand of political correctness and its fervor for cancellation of heretics is no less injurious to art. As in Miłosz’ time, “before it leaves the lips, every word must be evaluated as to its consequences. A smile that appears at the wrong moment, a glance that is not all it should be can occasion dangerous suspicions and accusations.” Neither writing nor science nor art nor film can survive the scourge of self-censorship with its integrity intact.

Writes philosopher Eric Hoffer of the “true believer” captured by a “mass movement”: he “does not create to express himself, or to save his soul, or to discover the true and the beautiful. His task, as he sees it, is to warn, to advise, to urge, to glorify and to denounce."

Of television writing, Substacker Wolfstar notes that it isn’t the inclusion of diversity that makes “woke” writing bad. It’s that it’s used to “cover up for the lack of absolutely anything else (like good plotting, characterization, logic, originality, compelling stakes).”

Insanely talented painter Gabrielle Bakker, whom I’ve interviewed and will profile in a future post, is similarly concerned. Our postmodernist culture, she says, values “equality and the amplification of what it sees as marginalized voices.” As a result, “Merit is chucked in favor of a malignant and unfair system of rewards giving many something they have not earned or passing over those who have.”

In the words of Miłosz: “What they prize as literature is nothing but its counterfeit. Repressed feelings poison every work, giving it a tinsel varnish which warns everybody: this is a synthetic product.”

I read "The Captive Mind" in 2023 and found it frighteningly apropos.

I'm a lifelong liberal, but I am increasingly appalled by the extreme ILliberality of my tribe. I've been ringing alarm bells about it for years.

Such people are, in fact, not liberal at all. They don't believe in classic liberal values; they believe in censorship and public shaming. They are smug, sanctimonious, condescending, and intolerant. They are as bad as the MAGA crowd. Two sides of the same coin.

As someone who 'drank the koolaid" and played around (to go easy myself) with shrill, scolding, so-called "didactic" art in the 80s, I see now how easy it was to critically undermine and cast that cloak of shunning over others than to dig deep for actual insight. In retrospect, I see how insecure I was, and fearful. I doubt I make better art now, but it's certainly messier.