I just started reading a book called The Elegant Witch, found in a used bookstore under the banner “Nostalgia.” It's a hardback, first published in 1952, and I was attracted to its glossy, finely illustrated book jacket and the lovely typography inside—something I've come to appreciate as a graphic artist who was trained just as phototypesetting started giving way to digital—a much visually inferior experience. On the cover, a woman clad in an ankle-length riding skirt grasps the reins of horse charging past a stormy and leafless forest, her cape flapping in the wind. I flipped through it, and finding it highly readable, brought it home on a whim.

More and more, influential people that I read and listen to speak of “curiosity.” Brené Brown calls curiosity a “superpower.” Molly Bloom, known for running famous poker games frequented by powerful male celebrities, told Jordan Harbinger that she won their trust by “[cultivating] an authentic curiosity” about them. And in a TED interview, Elizabeth Gilbert speaks of the importance of following the “gentle impulse” of curiosity. She tells about starting to garden on a whim, then investigating the origin of some of her plants, then ending up in Tahiti “exploring the history of moss,” and finally weaving it all into a novel about a nineteenth century female botanist. Creativity “comes in whispers,” Liz says, but can “grow thunderous.”

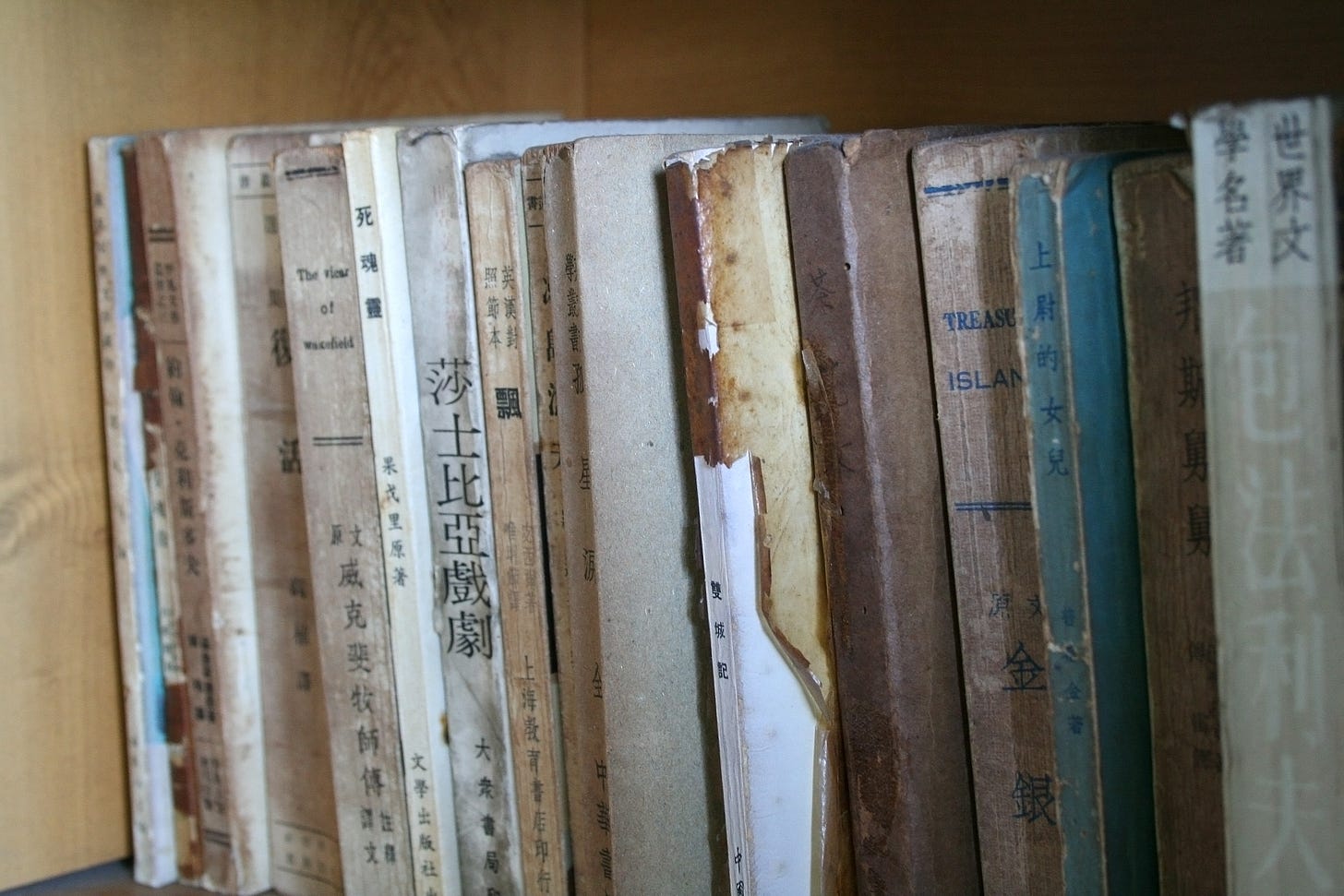

It is against the backdrop of Liz's advice that I stopped fighting the impulse to carry home vintage books, especially children's books, from the used bookstore I pass on my daily walk, having previously feared it a pointless and time-wasting endeavor. But what's up with that? I waste plenty of time on activities with far less promise of enrichment. The Internet, for example.

Also, some nonfiction author opining on our attention-challenged age, whose name I've now lost, said reading fiction makes you smarter, and another speaker I also cannot name recommended reading books, especially “old ones,” as an antidote to modern ennui. I think he meant classics. But there was really no reason, in the end, to resist bringing home Miss Twiggley's Tree by Dorthea Warren Fox, a book I would find beautiful, refreshingly feminist, and inspiring—it's giving me an idea for my next project.

I assumed The Elegant Witch, by contrast, would be some forgettable pulp novel. But whatever—Liz said it was ok. Turns out it's a rather beloved work of historical fiction, based on the 1612 Pendle Witch Trials, that's been in print since its inception. Its English title is Mist Over Pendle, and its English author produced another fifteen books.

And I've been thinking about the Renaissance. It's been a minute since I took that class, so forgive my superficial treatment. The Renaissance followed the Middle Ages, a time of famine, war, a theological focus in art and literature, and witch trials of the aforementioned sort. People began to crave deep knowledge, so they returned to the almost forgotten scientific and mathematical texts of the ancient Romans and Greeks. There's a lesson for our times. A parallel, even.

Maybe picking up crusty old books is not the absolute worst use of my time.

I've been casually researching the American Revolution and history of the Constitution, mostly to figure out what my own perspective on all of that is--since it's obvious from my ideological surroundings that I am expected to have exactly one. Along the way, to lighten the load of "The Federalist Papers," I picked up a copy of "Johnny Tremain," the children's book by Esther Forbes, which is set in the early days of the Revolution, in Boston.

Which then led to me picking up another book by Forbes, for adults, that had won her the Pulitzer Prize back in 1943: "Paul Revere and the World He Lived In." The book was transporting--and not just because it portrayed this bygone era so vividly. It was transporting because it did not try to impose a modern perspective *on* that era. The perspective, I sensed, was always Forbes' own. There was no attempt being made to impress a scholarly collective by matching their intellectual 'dance moves' step by step--not even one from 1943! There was only Forbes, who had researched the hell out of this period, and had a thing or two to say about it.

Point being, it's one of the most memorable things I've read in years, and I found it by wandering around. It's also utterly unmoored from this insistent era, in every possible way. A welcome reminder that the world we're currently occupying, which seems to scream "it will always be this way" louder than any other possibly could, will one day be accessible only through books like these.

Speaking of books ...🙂, your recent one in particular, I read through an excerpt of it over at Broadview, and thought to comment briefly here on it.

One thing -- of several things -- that leaped out at me was your "But set theory is probably the wrong framework for this discussion." Which seems obliquely related to your post "On forgiveness" in which you say, "... plain language. At a time in which the definition of basic terms (such as “woman”) are in dispute ...." In passing, transgenderism seems a rather bizarre phenomenon in many ways, and Jamie's "evil intent" may possibly be typical of those whose delusions are not endorsed by their "audience".

In any case, speaking more to your "set theory", you may have some interest in my post on the question of, "What is a woman?" in which I attempt to answer it by using some basic principles of categories and categorization. Unfortunately, such "plain language" tends to be somewhat "unpopular" since it really doesn't comport well with the illusions of many -- both women and transwomen -- by which there is some "mythic and immutable essence" to the category:

https://humanuseofhumanbeings.substack.com/p/what-is-a-woman